Young people in the village of Bunyakiri, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By helping young people to develop positive beliefs and attitudes, a USAID project can prevent future acts of violence, and contribute to peace and equity in DRC.

J. Harris, International Medical Corps

Young people in the village of Bunyakiri, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By helping young people to develop positive beliefs and attitudes, a USAID project can prevent future acts of violence, and contribute to peace and equity in DRC.

J. Harris, International Medical Corps

Young people in the village of Bunyakiri, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By helping young people to develop positive beliefs and attitudes, a USAID project can prevent future acts of violence, and contribute to peace and equity in DRC.

J. Harris, International Medical Corps

Young people in the village of Bunyakiri, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). By helping young people to develop positive beliefs and attitudes, a USAID project can prevent future acts of violence, and contribute to peace and equity in DRC.

J. Harris, International Medical Corps

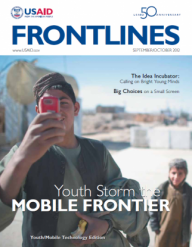

Gender-based violence prevention program targets youth with messages of equality in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Most of the girls and boys of Bunyakiri High School in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have spent their entire lives at the center of one of Africa’s most brutal conflicts.

Even after the 2003 ceasefire between the government and the largest rebel groups—including the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, the Congolese Rally for Democracy, the national opposition parties and others—South Kivu province has been plagued by outbreaks of violence among rival armed groups.

Sexual violence has become a constant threat for women and girls—many of them under age 18. Hundreds of young girls have reported being victims of sexual violence in eastern DRC, where rape is considered an epidemic. But the actual number of victims is likely much higher. No teenage girl wants to face the social ostracism that can come with surviving a sex assault. And, while less publicized, domestic violence and early and forced marriage also add to an environment of inequality for females in this region.

Since 2002, USAID and its partners have been working to improve services to sexual assault survivors in eastern DRC. While treatment is crucial, the Agency is also now working on prevention with a project designed to change attitudes and behaviors among the next generation.

The program, implemented by the International Medical Corps, started in 2010 and is based on an understanding that young people are still developing ideas about gender and relationships, which tend to be more engrained in adults.

“By engaging young people to develop positive beliefs and attitudes, the project can prevent future acts of violence, and can ultimately contribute to a more peaceful and equitable future for DRC,” commented Alessia Radice, International Medical Corps’ senior behavior change communications adviser in DRC.

Sensitization in Soccer

The effort works like this: Girls and boys between the ages of 10 and 16 are invited to participate in several activities such as mobile educational movies, sensitization sessions, quizzes and soccer matches for girls. The mobile cinema educational films address rape and sexual violence. The screenings are followed by discussions, led by trained facilitators, to help young people consider the causes and consequences of violence. Sensitization sessions help to increase young people’s awareness of their rights, explore inequalities in their communities, and challenge dominant attitudes around gender norms and masculinity. Quizzes give girls and boys a chance to show off their knowledge of sexual and gender-based violence while also encouraging discussion around the subject.

Though the events are kid- and teen-friendly, they relay important information, including laws that prohibit forced marriage for children under age 18 and where survivors of sexual assault can find help.

“We have to be sensitive to how we approach discussions on sexual violence when speaking to young people, but I am constantly amazed at how enthusiastic and committed to action these boys and girls are,” said Radice. “The participatory and entertaining format of the activities is often what attracts young people—playing soccer, competing in quizzes, watching movies and so on—but they are also genuinely interested in the issues. There are always requests for more sessions and we hear the young people talking about the messages outside of the formal activities. Informal exchanges with their peers is where these issues really come alive for young people, and it’s where the deep-rooted change is likely to come about.”

Early childhood experiences influence the likelihood of people later becoming perpetrators or victims of sexual violence, so it is important to give young people the tools to break away from this cycle of violence. In Bunyakiri, for example, domestic violence is viewed as normal to the extent that parents expect their daughters to be beaten by their husbands. Therefore, young people who witness these acts of violence on a regular basis need to be provided with alternative views of gender, masculinity and human rights.

Related Content

Creating An ‘Epidemic’ of Respect

Bunyakiri is an isolated village, more than a two-hour drive from the nearest big city, along dangerous, muddy roads and nestled in a valley surrounded by dense Congolese jungle. At the high school here, children say they are absorbing the lessons from the project.

“I know that we must not reject women who have experienced sexual violence or, if they have HIV, we should still welcome them into our homes,” said Solange*, a 10th grade girl.

“Marriage when you are younger than 18 is forbidden. I have spoken to my parents about this and have told my younger sisters so that none of them will make the mistake of getting married too young,” said Lucien*, a 10th grade boy.

“In this sense, project participants are expected to become champions against gender-based violence within their families and communities. With the help of USAID, the next generation of students at Bunyakiri High School may grow up free from the threat of gender-based violence,” Radice said.

A project that seeks to bring about such a significant shift in attitudes and behaviors inevitably faces many challenges. Low participation by girls was a particular problem, and the International Medical Corps has been finding innovative ways to encourage more young women to get involved, such as initiating the girls-only soccer matches.

Once the young people are informed of their rights, girls, especially, become upset about the inequalities they face. One girl who attended a sensitization session in Bunyakiri became very upset that her four brothers were going to school while she and her two sisters had to work in the fields to earn money to send them there, recalls Florence Iloko, an International Medical Corps community mobilizer working on the project.

The project in Bunyakiri has worked with over 900 young people to date directly through sensitization sessions and activities. More than 7,500 community members have come along to support the teams during the girls’ soccer games. Similar projects are currently underway in five other sites across eastern DRC, reaching thousands of young people from across the region.

While formal impact assessments have not yet been conducted, community leaders have reported a reduction in forced and early marriage since the program began.

“The most obvious change I have seen is that the girls don’t let the boys tell them what to do anymore,” said Jean Marie Katangwire, 49, principal of Bunyakiri High School.

Josh Harris is with International Medical Corps, based in Los Angeles.

*Last names of individuals under 18 years old have been withheld to protect identities.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.