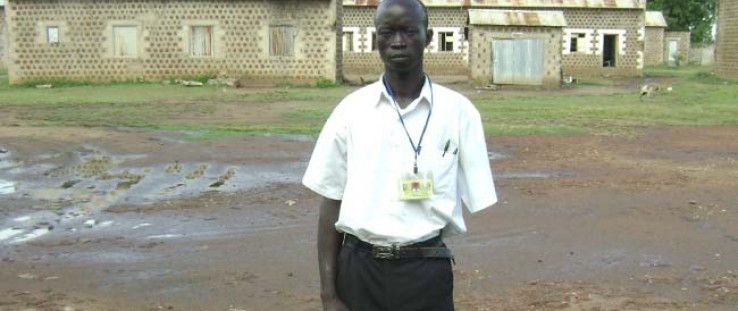

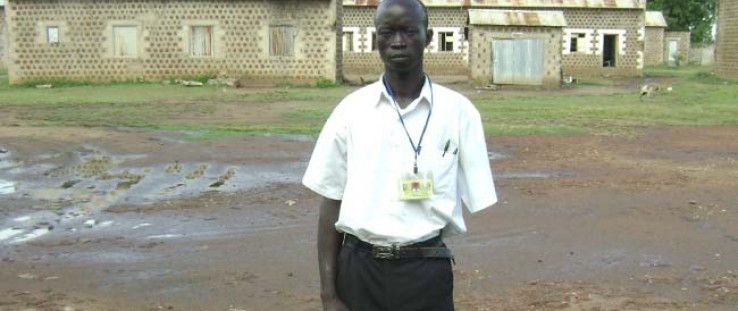

Gilaso Odong, 19, lost an arm as a child soldier but now receives USAID support to study at Torit Secondary School in Eastern Equatoria.

Education Development Center

Gilaso Odong, 19, lost an arm as a child soldier but now receives USAID support to study at Torit Secondary School in Eastern Equatoria.

Education Development Center

Gilaso Odong, 19, lost an arm as a child soldier but now receives USAID support to study at Torit Secondary School in Eastern Equatoria.

Education Development Center

Gilaso Odong, 19, lost an arm as a child soldier but now receives USAID support to study at Torit Secondary School in Eastern Equatoria.

Education Development Center

On a continent that already faces significant challenges in education, those confronting South Sudan are especially severe. For decades South Sudanese have been fleeing conflict, fighting, sheltering in refugee camps, or simply struggling to survive in their villages and towns as a result of war throughout Sudan that plagued the south since before Sudan gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1956.

While delivering education services in this environment was possible in certain areas, entire regions missed out on these opportunities. According to the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics, and Evaluation, only 27 percent of South Sudanese adults today are literate. This puts South Sudan around the bottom of the list of world literacy and presents an enormous challenge both for the Government of South Sudan and for USAID and other organizations seeking to help South Sudanese to recover.

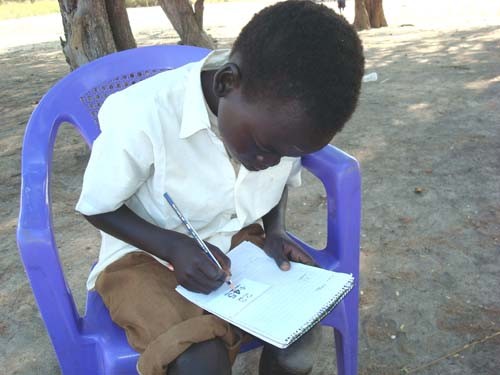

Many schools were reduced to rubble during wartime, and when an accord was reached through the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), South Sudanese children commonly attended lessons held outdoors and taught by teachers who lacked formal training and a standard curriculum. Even now, 72 percent of the 19,872 primary level learning locations across South Sudan are under a tree or other non-permanent structure rather than in a schoolhouse, with children of various ages learning together. In many cases, students have no books, writing materials, or desks, and a teacher’s equipment is typically limited to a small chalkboard and chalk.

The obstacles to quality education do not stop at classroom logistics. Of more than 26,000 primary school teachers in South Sudan, 84 percent are not certified to teach, and only 12 percent are women. In a post-conflict economy with limited public revenue and almost no sources of private sector employment, three-quarters of the national budget goes to public salaries, while 6 to 7 percent is spent on education. The lack of literacy hinders South Sudan’s capacity to govern—nearly one in four civil servants in the country lacks a formal education.

Despite Obstacles, Enrollment Gains

Despite the many roadblocks, significant gains in education have been achieved since 2005. With USAID assistance, primary school enrollment in South Sudan has increased from approximately 300,000 students in 2000 to 1.4 million in 2010. USAID supported the construction or rehabilitation of 140 primary schools and five secondary schools. To improve teachers’ skills, the Agency supported the rehabilitation of four regional teacher training institutes and is encouraging women to become teachers. To address lower literacy and school attendance among girls, USAID has awarded over 9,000 scholarships in the past five years to girls and disadvantaged boys who are unable to pay school fees. Secondary school fees range from $28-$50 per school term.

Sylvain Sumurye, of Kajo-Keji County in Central Equatoria state, received one of USAID’s scholarships. Previously, she had dropped out of school due to an early pregnancy and was abandoned by her husband.

“Barely three months after I gave birth, my husband got another woman and started beating me and eventually abandoned me with a small child of six months,” said Sumurye, now 25. “Helplessly, I decided to go back to my parents. After the signing of the CPA, I went back to school and forgot about my husband. I studied hard and successfully completed my secondary education and joined Kajo-Keji Teachers College in 2009.”

The Teachers’ College has benefited from a USAID school improvement grant. These funds are generally used for rainwater harvesting and storage, dining hall dishes, and helping to improve the skills of school governance bodies.

As part of its efforts to improve school attendance among girls and young women, the USAID scholarship includes “comfort kits” for female students comprised of sanitary pads and other hygiene supplies. “During my periods, I used not to attend class because I did not have money to buy sanitary pads. I pretended that I was sick and opted to remain in the dormitory for three to four days. Thanks to USAID, I was given comfort kits, which helped me a lot because I could attend all my classes without worry until I completed my school and graduated in 2010,” Sumurye explained.

To support young women like Sumurye to continue their education even after they have children, female dormitories are fitted with separate rooms for mothers to attend school with their children.

After graduation, Sumurye was hired as a fifth-grade geography teacher at Kiri Primary School. With the money she now earns, she can afford to pay for her daughter’s school fees and uniform as well as better housing. “Education is the key road to success,” Sumurye said. “I advise all South Sudan women to go to school so that they are not deprived of their rights.”

Investing in Girls, Child Soldiers, Returnees

USAID/South Sudan Mission Director Kevin Mullally, who previously served as mission director in Senegal and Rwanda, noted that girls’ education is a priority for USAID.

“Research has shown that educating girls offers a tremendous return on investment in a developing country. It leads to healthier families, which are a critical component for future growth and success,” he said, adding that education can also aid South Sudan recover from war. “Education provides disaffected girls and boys with the confidence that they can move forward in their lives, in spite of what the people of this country have experienced.”

Former child soldier Gilaso Odong, of Torit in Eastern Equatoria state, is among the young men who received USAID scholarships. He was abducted at age 10 and forced to fight, losing an arm to a gunshot wound. He became a refugee in Kenya before returning to South Sudan three years ago.

“My parents cannot afford to pay my school fees,” Odong said. “I thought, ’I am back home, but still in a miserable life.’ I lost my arm during the struggle and I thought, ’the peace has come, I will have free education,’ but still I did not see any changes in my life.” Now age 19, he was able to continue studies he began as a refugee with the help of a USAID scholarship and has one year left until he graduates from Torit Secondary School.

Radio-Based Learning

One of USAID’s most important tools in raising literacy and improving learning in South Sudan is radio—the medium that reaches the broadest segment of the population of more than 8 million. USAID uses radio-based learning not only to provide teachers with lessons they can present to their students but also to reach non-traditional, generally older students who may not have had the opportunity to attend school.

In 2010, USAID’s radio-based learning programs have reached nearly 100,000 students and 445,000 youth and adults who did not have access to regular school instruction. The USAID-supported South Sudan Interactive Radio Instruction has broadcast over shortwave, FM, and through MP3s since 2005, programming that also includes civic education programs. Community radio stations that USAID supports also broadcast the Agency’s radio-learning programs.

USAID is reaching out to communities to support educational access in a variety of ways. For example, the Agency is helping parents contribute to decisions that affect their children’s education, while local authorities become better informed about their constituents’ priorities. To help county education officials in remote parts of South Sudan inspect far-flung schools and interact with their employees and students, USAID has provided motorbikes so education inspectors can make regular visits.

With education among the highest priorities for citizens of South Sudan, USAID is working to ensure the quality and availability of education services, improving opportunities for Southern Sudanese as they build their nation.

As South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir Mayardit said in a speech to the South Sudan National Assembly on Aug. 8, “We must now focus on the delivery of basic services to meet the expectations of our people.”

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.