Keeping water clean for up to 72 hours

Jonathan Kalan

Keeping water clean for up to 72 hours

Jonathan Kalan

Keeping water clean for up to 72 hours

Jonathan Kalan

Keeping water clean for up to 72 hours

Jonathan Kalan

Diarrheal disease, a leading cause of death for children under 5, is responsible for nearly 1 million deaths per year in that age group alone. Many communities seek solutions through protected communal water sources, or, if they can afford it, water pipeline systems. But these systems are ineffective when clean water at the source is stored in the household and re-contaminated with a dirty cup or an unwashed hand.

Use of chlorine, by contrast, keeps water safe for drinking for a minimum of 24 hours without recontamination. Purifying chlorine packets are available in household packages in retail stores, but the use of chlorine remains low, especially among the poor. In one Kenyan study area, for example, researchers from Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) found that less than 10 percent of households regularly use chlorine, despite the low monthly cost of approximately 30 cents and several years of vigorous social marketing to raise awareness about the product.

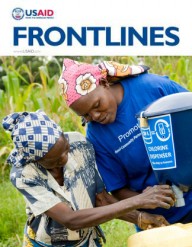

Using randomized control trials, the Dispensers for Safe Water program at IPA evaluated ways to change behaviors and increase the uptake of chlorine. The evidence demonstrated that minor adjustments in the way chlorine is delivered have major impacts in uptake. Distributing tablets in easy-to-use containers at communal water sources, as opposed to household-level packets, serves as a reminder and creates public norms around the use of chlorine. A randomized trial in Western Kenya found that 50 to 61 percent of households in the treatment group with public dispensers adopted the water treatment, compared with only 6 to 14 percent in the control group.

With $5.5 million in Stage 3 support, Dispensers for Safe Water is scaling dispensers in Kenya and Uganda, and has plans to add more countries to that list. The project aims to provide up to 5 million people with access to dispensers over three years.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.