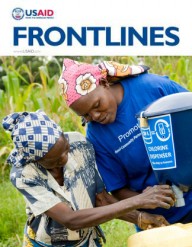

USAID’s Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction project provides training in first aid and first response for communities vulnerable to natural disasters.

Luke Bostian, Aga Khan Foundation

View More Photos

USAID’s Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction project provides training in first aid and first response for communities vulnerable to natural disasters.

Luke Bostian, Aga Khan Foundation

View More Photos

USAID’s Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction project provides training in first aid and first response for communities vulnerable to natural disasters.

Luke Bostian, Aga Khan Foundation

View More Photos

USAID’s Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction project provides training in first aid and first response for communities vulnerable to natural disasters.

Luke Bostian, Aga Khan Foundation

View More Photos

In an Afghan village at a crucial point in a performance known as Theatre of Change, a young man challenges a village elder to reconsider his view of fate. For generations, Afghanistan has suffered devastating floods, landslides and earthquakes, including two quakes in 1998 that claimed 6,500 lives. In a country where half the population of about 31 million lives at risk from at least two kinds of natural hazards—not to mention wartime hazards—a certain resignation becomes second nature. But the young man onstage challenges that, saying, “We accept that Allah is all-giving and all-knowing, but the Koran also says that it’s every person’s responsibility to do what they can to safeguard their lives.”

The theater performance gives the village a chance to gather for entertainment but it also leads people to consider core questions from new angles. A growing consensus in international development holds that empowering remote communities to reduce their vulnerability to natural hazards saves far more in the long run than it costs, and is essential to preserve development gains.

National governments play a key role in disaster preparedness and response, but they face constraints. Projects like USAID’s Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction (CBDRR), implemented by the Aga Khan Development Network, help bridge the gap in services by informing communities about disaster-conscious planning and improving their ability to be first responders when disasters strike.

With nearly $5.3 million over five years (2009–2014), CBDRR builds this local capacity through community emergency response teams, known as CERTs. But before it can begin the community-level planning and training, the CBDRR team, comprised almost entirely of Afghans, must persuade people that the community can actually take action against natural disasters.

“Many in these communities think that this is something they can’t do anything about, that disasters are something from God that they just have to live through,” says Tameeza Alibhai, policy manager for the Aga Khan Foundation in Afghanistan. “It’s very hard to have people consider preparedness for disasters as a priority.”

Firoz Verjee, coordinator of the Disaster Risk Management Initiative of the Aga Khan Development Network, agrees that fatalism can be a hurdle to reducing the deadly damage of future disasters. He says that it often stems from an unclear understanding about what causes natural hazard risk, and what practical actions can reduce that risk.

“Major earthquakes are a geological certainty in these areas in Central and South Asia,” says Verjee. As he explains, DRR helps remote communities “make investments that they need in their homes, workplaces and schools to be much safer.”

Sometimes in the village theater, the older gentleman onstage refuses to heed the younger man’s early warning signs. Then when disaster strikes, the audience sees what happens. Still, it’s also entertainment. “In the end, there’s a feel-good place and the outcome is always positive,” says Alibhai. “For people whose days are taken up with daily subsistence, the play allows them time to laugh, to break up their day. And it has an impact on mindsets.” Alibhai calls the performance “one of the more fun ways we use to help people internalize these concepts and take ownership.”

Readiness Is All: How It Looks on the Ground

So far, the project has formed 96 CERTs in 96 villages across Baghlan and Badakhshan provinces, each comprised of about 25-30 people. “Those community emergency response teams are voluntary, and they are our first line of response,” says Verjee.

Project staff works with communities for months to form CERTs and guide local assessment toward a customized plan, with actions that may range from infrastructure – a new flood channel or retention wall – to first-aid and first-response training. Khan Mohammad, a staff disaster risk specialist with Focus Humanitarian Assistance, says, “My moment of greatest job satisfaction is conducting a preparedness plan and recommending solutions.”

In one instance, the project team assessed a debris channel where flash floods passed. The team, including a geologist and structural engineer, walked with about 15 members of the local leadership council, or shura, along the channel, asking when a flood last came through and the kind of debris it left. The DRR plan grew from that local knowledge.

Some see the benefits right away. Abdul Aziz, a 26-year-old in Badakhshan, first learned of DRR during a meeting with project staff and quickly realized it was good for his remote village, which lacks access to health facilities.

Likewise in Lokhtoghai, a village in Baghlan province, where Sayed Ahmad grew excited about the possibilities from the first meeting, and he joined the local planning group. “We need to be the first responders to help ourselves,” Ahmad says. They have seen payoffs from first-aid training and flood preparedness again recently, when a flood struck part of the village and drew an immediate response from CERT members with shovels.

Lokhtoghai also established a School Emergency Response Team, or SERT, involving students. This helped last year when SERT members used their first-aid skills to help a child injured during a flood. In Baghlan villages, too, young men and women are quick to demonstrate their new skills, including CPR.

USAID also supports other community-level Disaster Response and Resilience (DRR) programs in Central and South Asia. In Nepal, for example, the Program for the Enhancement of Emergency Response (PEER) has trained hundreds of emergency responders in “search and rescue” techniques for collapsed structures and in medical first response skills. Over the past three years, USAID has provided approximately $30 million to support disaster response activities in Afghanistan that incorporate DRR elements such as training for disaster-prone communities, pre-positioning of relief commodities in remote areas, and hazard mapping.

Gender and Disaster Planning

In places like Afghanistan, involving women in the disaster preparation work is both challenging and essential. Social conditions often marginalize women and girls, and they face greater risks in the wake of disasters, including an exacerbated risk of being trafficked for forced labor or the sex trade, says David Molden, director general of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development in Nepal.

After Nepal’s Koshi flood in 2008, he notes, many men left to find work in India, leaving women like Samitra Devi behind because they lacked skills for off-farm work. So Devi and other women took on the role of household heads in addition to their usual responsibilities, and struggled to protect girls from lurking traffickers. “In many cases, women’s needs for economic development and social support are overlooked by disaster relief and rehabilitation initiatives,” he writes.

Aga Khan’s Alibhai says women are interested in her travels throughout the country. During a visit to a conservative village where women stay indoors when outsiders come, Alibhai met first with the CERT, then with the local women. “They were very gracious,” she said.

Through an hour and a half discussion, the women expressed their interest in the flood mitigation project. One older woman described what happened during floods, the panic of seeing her home fill with water: “We have to grab everything we can and move to higher ground. And there are no structures up there.” Then they may have to live in the open for weeks until the floodwater subsides. The women articulated why they needed mitigation efforts, and what they wanted for their children.

“Just because women are not in the forefront of the discussions, that doesn’t mean they don’t know what’s going on,” Alibhai concludes. “Often they know what they would like to see happen, and they are not shy about lobbying for their needs.”

To facilitate this, program staff includes women organizers like Fatima Akbary, who works with CERTs on rapid assessments of a community’s social, cultural, and economic life and its disaster vulnerability. She writes in an email: “I travel four times to each participating village, where we: (1) Conduct rapid assessment, (2) Conduct a detailed assessment, (3) Hold village seminars, and (4) Facilitate the monitoring and evaluation process.” At each step they aim for gender balance, she explains, “but the mode of participation varies depending on the village. In some villages men and women can meet together in one place; in other villages local custom dictates that they meet separately.” She adds, “I know that these precautions save lives and homes.”

These precautions get woven into the village theater, which, besides changing mindsets, can include details that come in handy later. Sayed Ahmad, the CERT member in Lokhtoghai, remembers when CBDRR put on the performance there. “One part of the show exactly matched the type of disaster that we experienced the other day,” he said recently, adding that it demonstrated “how to handle types of injuries that can occur during floods.”

David Taylor and Luke Bostian are with the Aga Khan Foundation U.S.A.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.