Local mothers in Matam report that, since changing over to enriched flour mixes, the children have been demonstrably healthier and more active.

Olivier Asselin

Local mothers in Matam report that, since changing over to enriched flour mixes, the children have been demonstrably healthier and more active.

Olivier Asselin

Local mothers in Matam report that, since changing over to enriched flour mixes, the children have been demonstrably healthier and more active.

Olivier Asselin

Local mothers in Matam report that, since changing over to enriched flour mixes, the children have been demonstrably healthier and more active.

Olivier Asselin

SENO PALEL, Senegal – Despite being a major producer of cereal in Senegal, Seno Palel, a region of about 425,000 people in the country’s extreme north, also has high rates of undernutrition—22 percent of the children are underweight and nearly 18 percent suffer from stunted growth.

The problem: Apart from staple grains, there’s not much else to eat. Due to the harsh climate, the few vitamin-rich fruits and vegetables that are cultivated locally are expensive and rarely become a regular part of villagers’ diets.

One solution: vitamin-enriched flour. In 2012, staff from USAID’s Yaajeende Food Security Project, part of Feed the Future, the U.S. Government’s global hunger and food security initiative, began to test the market for fortified food products and iodized salt to gauge the level of interest in Seno Palel and its surrounding villages. Surprisingly, demand was much stronger than anticipated.

Enriched flour—which essentially blends regular corn flour with other pulverized, vitamin-rich ingredients like black-eyed peas, peanuts, millet, jujube and baobab, can be found in larger urban areas, but not in rural areas where the high cost of transportation makes regular use by villagers too expensive.

In response, USAID began engaging community nutrition volunteers (CNVs) to train women’s groups to enrich their own flour. USAID’s Feed the Future agro-nutrition project trains CNVs like 43-year-old Raky Mamadou Niane, who works with 15 women’s groups in the villages around Seno Palel in the Matam region.

Together, 225 women of Seno Palel have established an enterprise known as Jab Gollade (The Working Women) to produce a nutritious, and reasonably priced, enriched flour mix.

“From the outset, we found that we couldn’t keep enriched flour in stock and customers were buying up everything that we could get our hands on,” said Adrien Ndour, a USAID staffer in Seno Palel who trains nutrition volunteers like Niane. “Sales went up so drastically, we began to have problems maintaining the stock.”

Using enriched flours to combat moderate and chronic malnutrition is not a new phenomenon. However, typically these flours have been provided by humanitarian agencies like the World Food Program. This is the first instance in Senegal where USAID has supported a local group undertaking commercial production of enriched flour as a revenue-generating enterprise.

Local demand for the flour mixes is strong because the activity is being conducted in concert with a package of activities aimed at changing the nutritional habits of women and young children in the village. USAID has organized 15 mother-to-mother groups, groups of 10 to 15 women who get together and share key information about maternal and child health and nutrition.

CNVs have also held a series of community meals in the villages during which people sample new foods, practice preparing nutritious recipes, and learn about nutritional issues such as the importance of ensuring that salt is iodized.

After two years of working together, these groups are now launching a range of income-generating activities like vegetable gardening, livestock raising, and the commercial production of enriched flour.

Fabricated using a range of formulas developed by USAID nutritionists, the enriched flours are mixes of locally available ingredients. Although the most popular flour is used to create porridge that is fed to infants and young kids, adults are now modifying it for use in their own morning lakh, a local cereal made of yogurt, cereal flour and sugar.

“The people are finding that it is more filling, better tasting and easier to digest than their traditional porridge,” Niane said. “They feel better after they eat it.”

“We are noticing that children who are eating the enriched porridge are having fewer problems with diarrhea,” said Bineta Bocoum, one of Jab Gollade’s founding members. “And it’s not only good for them, it tastes better too. They like it so much the children are refusing to eat traditional porridge. And they’re getting fatter.”

Binta Diafara Daff, a local mother, has been using the flour since December 2012 when she took her 15-month-old son, Dewel Boucoum, to the local clinic and found out that, at 13 pounds, he was malnourished and at risk for long-term health problems. Daff began feeding Dewel 100 grams of the flour mixes three times a day. Within three months, Dewel had gained more than five pounds, bringing him up to the normal weight for his age.

“I don’t have to take him to the hospital so often,” Daff said. “He isn’t sick as much as he was, and that means I’m spending less than half of what I used to in doctor’s fees.”

Dewel’s case is part of a larger trend. The Senegalese Committee for the Struggle against Malnutrition recently conducted surveys that showed a significant drop in the number of cases of moderate and acute malnutrition in the villages around Seno Palel—from 30 cases in 2011 to 10 in 2012.

Not every community shows such a high level of demand for a commercially produced product, however. In areas where interest is not so high, often for financial reasons, USAID provides training on how to enrich flour at home, for example, by adding roasted grains to the family's flour mix. For families who don't understand the value of enriching flour, USAID provides sensitization workshops that explain the nutritional benefits of the process and the positive impact on children's health and growth.

A Booming Local Enterprise

With the help of a grant from USAID, the Jab Gollade women use artisanal techniques to produce and package 50 kilograms of flour per day. The women purchase ingredients like cereals in local markets in surrounding villages Kanel and Sinthou Bamambé. First, they hull and winnow the grains, ensuring that only the best quality grains are retained for the flours.

They then wash and dry the grain and then take it to a local mill for grinding. Following their training from USAID, they then compose a range of mixes using precise measurements, and package the mixes into 100-gram packets which are hermetically sealed. Each packet sells for around 50 cents on the local markets, bringing the business about $90 profit per batch.

Other development agencies recently placed orders with the women, including a local health program that ordered 1.5 metric tons of enriched flour. It took the women nearly a week to fill the order, but it earned them almost $1,600 in profit, a considerable amount for seven days’ work in an area where a farmer’s average monthly income is about $40. As the popularity of the product grows, an expanded customer base is expected to further increase the women’s incomes.

Divided among the group’s members, the money goes into a revolving loan fund that supports women’s enterprises within the group. The remainder is divided up among the women and used for everyday items like food, soap and other household goods.

“This project has worked so well because it is generating a fair amount of revenue for these women,” said Niane. “Seventy-five more women have recently requested to join our group. Now the members are talking about diversifying our business into other areas such as selling iodized salts and vegetable-based products.”

USAID staffers are working with the women to co-finance an expansion, create a business plan and access financing so they can purchase equipment to scale up further. More innovative packaging solutions are also being discussed to reduce costs and eliminate the waste that comes from single-use plastic sachets.

“The example of Seno Palel points the way forward for nutrition interventions because it is an example of a social enterprise that generates revenue for these women, but also provides a range of health dividends for the entire community,” said project director Todd Crosby. “It is a sustainable solution that at once improves the community’s health and increases its wealth, which ensures that these beneficial products will be around for a long time to come.”

Engineering a ‘Marketplace’ for Healthier Foods

East Africa is home to 23 million children who grow up stunted, or underdeveloped due to poor nutrition. Stunting leaves them permanently impaired—both physically and mentally—and it costs countries up to 3 percent of their GDP every year.

“Undernutrition is an underlying cause of one in three child deaths, and a child who is undernourished grows up to earn less, and is thus more likely to live in poverty,” says Tom Hobgood, Feed the Future team leader in Tanzania.

Even so, for years, development priorities did not robustly link nutrition to agriculture, or incorporated it as just one component of health. But now, countries throughout East Africa have begun to address nutrition as a priority. And through President Barack Obama’s global hunger and food security initiative, Feed the Future, the U.S. Government is supporting nutrition as a prerequisite to success in the region’s food security.

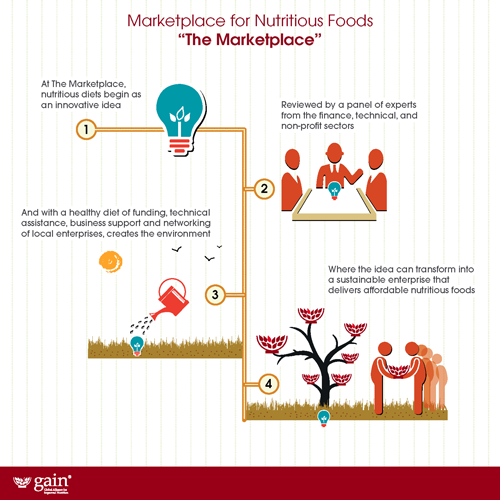

One new development that links farmers to markets through a common vision of making nutritious foods more available, is the Marketplace for Nutritious Foods. This network and finance platform encourages the development of local food businesses that will give farmers incentives to grow healthy foods, processors incentives to manufacture nutritious foods, and will give consumers incentives to buy and eat them. This can mean, for example, that a farmer grows more nutrient-rich orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, or that a consumer gains access to dairy products.

The Marketplace, led by the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), was created in 2012 with an initial grant of $ 2.1 million from USAID under Feed the Future. Already launched in Kenya and Mozambique, and soon to arrive in Tanzania, the Marketplace will invest in companies with sound business plans that are sustainable, scalable, and feasible given the market, and ultimately that introduce nutritious foods affordable to all populations. Local enterprises submit applications, and those chosen by the Marketplace’s panel of experts receive start-up funding, technical help and access to an exclusive network of investors and business mentors.

“The difference between the Marketplace and other agribusiness development programs is that it is focused on bringing nutritious foods to local markets, while not losing sight of productivity and income improvements for entrepreneurs,” says Marc Van Ameringen, executive director of GAIN, which manages the effort.

“Consider the Marketplace as a pipeline for investors and local agribusinesses facing obstacles that prevent more nutritious foods from reaching local markets. There is real opportunity for the Marketplace to increase private-sector innovation for local populations,” adds Bonnie McClafferty, GAIN’s director of agriculture and nutrition.

In Mozambique, for example, where 94 percent of agricultural production comes from smallholder farmers and only one-third of those farmers grow any vegetables, the Marketplace will focus on driving demand for foods with greater nutrient density, such as orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, soy-based foods, animal protein and dairy products.

Over the next few months, the Marketplace is expected to select its first batch of eight to 10 awardee enterprises in Kenya and Mozambique, with Tanzania issuing its first call for proposals in June. If the Marketplace is successful, within five years many more families across the entire region should have access to affordable and diverse foods to eat.

For more information on the Marketplace for Nutritious Foods, please contact marketplace@gainhealth.org.

Comment

Make a general inquiry or suggest an improvement.